Cycling for transport is often seen as an urban solution, but it can solve some of our rural transport issues too. So, what are some of the issues in our rural places?

Motoring has subsumed the road network which means that cycling between rural places takes place on roads where driver speed and traffic flows are high; or rather cycling doesn’t take place unless it is a leisure activity pursued by the fit and the brave. The highway networks are also highly variable and a quiet rural lane can easily give way to a thundering A-road with no safe means of crossing to the next rural lane.

The lack of rural transport options means there is a certain level of enforced car dependency and therefore transport poverty; especially where the distance to access services is much further than in the urban context. We shouldn’t forget about tourism because while it helps to support rural economies, there are the knock-ons created by people driving to and around places. This in turn adds to the poor conditions for cycling on rural roads.

If we are to support rural communities, there needs to be investment in transport, but because we are often dealing with low population densities, the costs of transport support can be high per head served. If we need to build infrastructure, we often have to deal with man-made and natural barriers which are increasingly impacted by climate change, and we have the challenge of construction costs where people, plant and materials have to be moved longer distances to work sites.

The other important issue facing rural investment is that business cases tend to favour the projects which are most likely to be used by the most people, and to some extent, those that do not cause time penalties to commuting drivers. Apart from making it harder to sell cycling as non-commuting transport, this crucially makes it harder to lever in finance for projects which might be as simple, but fundamental, as building a new shared-use path between two village because the current road link is terrifying to use. This “pioneer” infrastructure performs the basic level of service that people driving already enjoy and we think the arguments should be framed like this rather the number of commuters per hour we’ll attract.

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

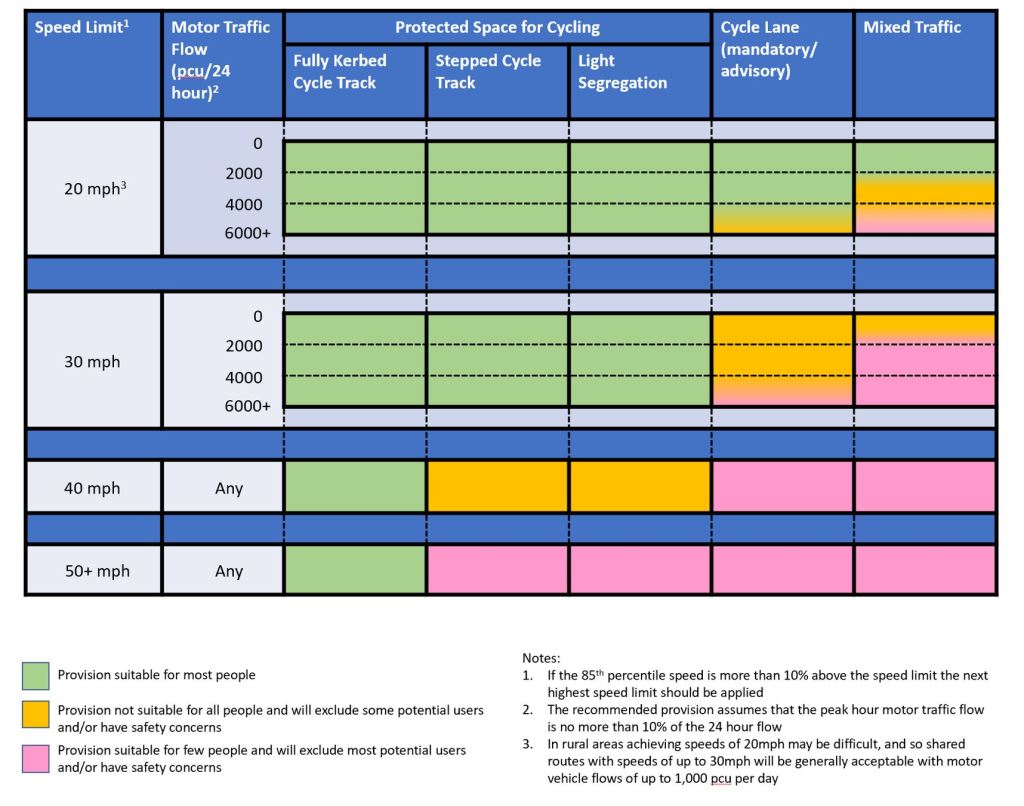

At this stage, it is worth reminding ourselves about the conditions which we’re designing for. In England, we have Local Transport Note 1/20 Cycle Infrastructure Design. Above Figure 4.1 from LTN 1/20 is reproduced and it gives us a good starting point to remember what conditions people need to want to cycle for transport. It can be a challenging table to apply to an urban context and so it’s more so in a rural context, although we would argue that the challenges are financial and political, not technical.

Rural situations already get some leeway in the notes which recognises the challenges of 20mph speed limits in rural areas, but the 1,000 Passenger Car Units (PCU) per day remains the key metric to think about because we know that people do not want to mix with fast and heavy traffic because we have undertaken countless pieces of market research that tell us this. We can use 20mph in rural places, but perhaps this will tend towards villages centres more often than not. PCU takes into account the impact of larger vehicles in traffic flows. For example, am HGV is taken as 2.3 vs a car being 1.0.

© CROW

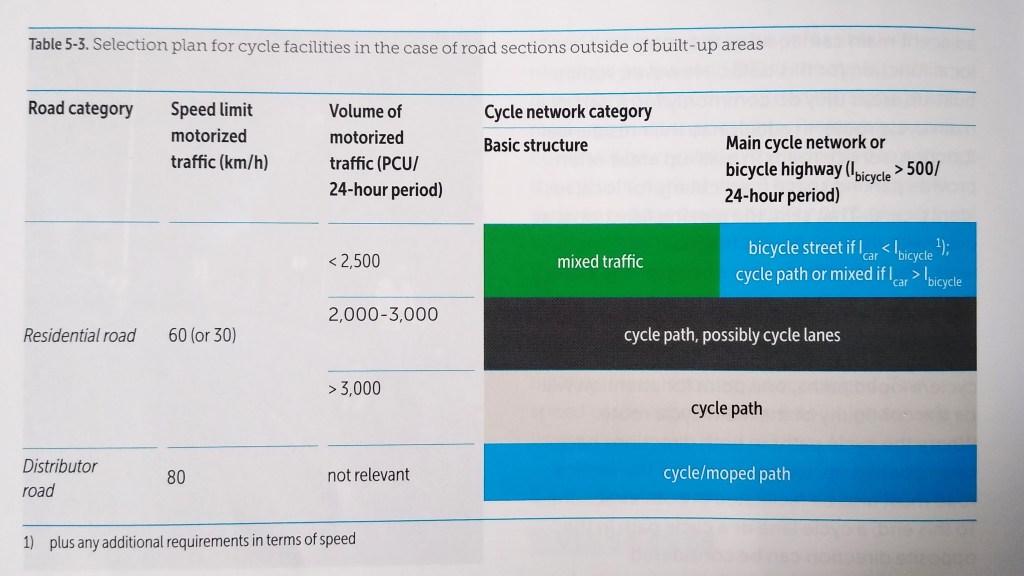

It’s worth looking at what a high-cycling nation thinks about rural road conditions. Above is Table 5-3 from the Dutch CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic which considers situations outside of built up areas. This both adds some nuance as it considers cycle network status. A basic road with less than 2,500 PCU per day at 40mph might be acceptable, although 20mph would be more favourable.

Traffic flows overlap and so once we’re into the 2,000 to 3,000 PCU per day we are really looking at cycle tracks with cycle lanes being a relaxation where there might be an interim requirement before something else is done. Once we’re over 3,000 PCU per day or at 50mph then there’s no debate, cycle tracks are required. It’s not UK guidance, but we would argue that it’s very useful in the UK rural context because the impacts of physics and biomechanics are not geographical.

It is very easy to get drawn into a debate about just providing routes; and as with urban places, we need to think bigger. Motoring has access to virtually everywhere which has pushed out cycling, and in rural places, walking and wheeling as well. We have a good motoring network by default and so we need to match this with with a good cycling network as a means to connect places for transport choice. Walking and wheeling can benefit in some locations which are closer to villages, but most people are not going to walk cyclable distances, and e-cycles are increasing that range for all sorts of people. Sometimes, it’s not even about cycling, walking or wheeling. It’s about nicer villages and places.

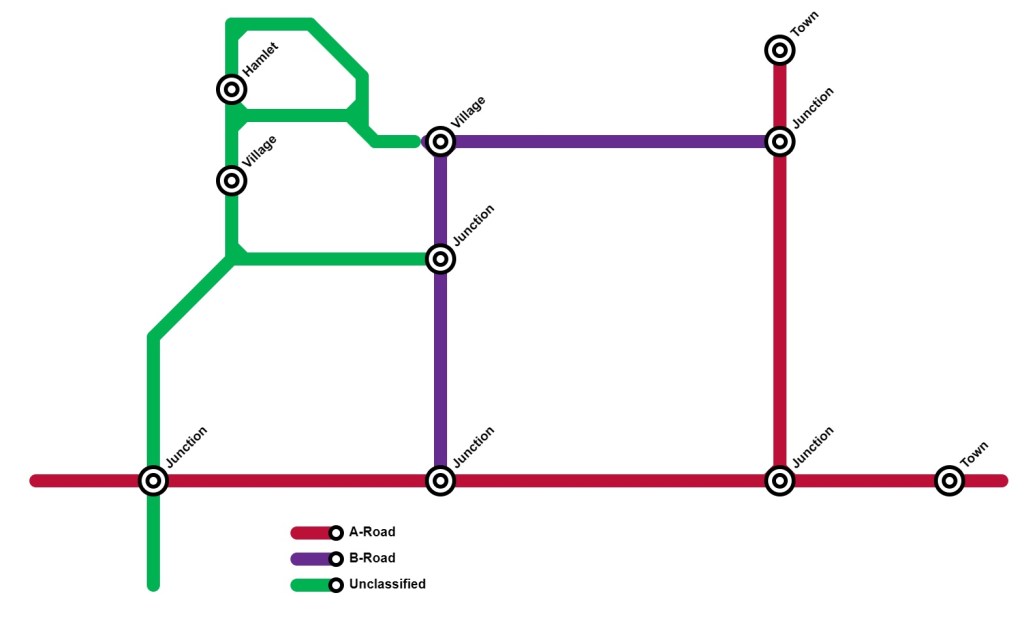

The image above is an example of a rural road network. It is based on a real place in the UK, but we don’t want to get bogged down in the local details so we’ll keep it generic and at the network level. In this model, we have full and unfettered motoring access and so even the unclassified roads are going to be highly variable for cycling between places, and potentially as variable in the villages and the hamlet for people walking and wheeling too. The A and B roads are most likely going to be so hostile as to be unusable by most people. This is where we end up relying on cars even when distances are perfectly cyclable.

People want and need to travel. Perhaps between the two villages, some day-to-day services are accessible and in theory, people’s needs could be catered for comparatively locally if they can travel between the two. Denser provision of services will be available in the towns and so we might not be thinking about daily needs, but weekly needs, but people still need to access them. Perhaps there are bus routes on the A and B roads which people could access as pedestrians or cyclists if only they could get to a bus stop safely – nothing requires us to concentrate on single modes.

In taking the network we have, we need to think about how it can or should function. This gives us several questions to think about:

- What should our flow roads, distributor roads and access roads be?

- Can we repurpose any roads or sections as traffic-free?

- Do we need to acquire land?

- Are there any interim solutions such as speed limit reductions, traffic calming, or restricting certain vehicle classes?

- Can the highway cross section be redesigned? This could include creating space for cycle tracks and running motor access in single directions with local loops?

- What is our speed limit strategy which considers perhaps what the Dutch guidance tells us?

- Can we filter any roads to make them access only to get flows right down?

- Where do we need crossings of main roads and what form should they take.

- Should we retain a road because it is strategic and build a parallel cycle track or even a parallel road which is filtered and provides safe access to than is currently provided by the existing road?

- Are we prepared to build new roads to unlock better outcomes. That doesn’t mean a full-flown high speed bypass to trunk road standards, it means shorts sections to bypass a village centre which could then be filtered and repurposed for public space.

- What about network resilience and maintenance, especially in the winter? This can equally apply to the motoring and cycling networks.

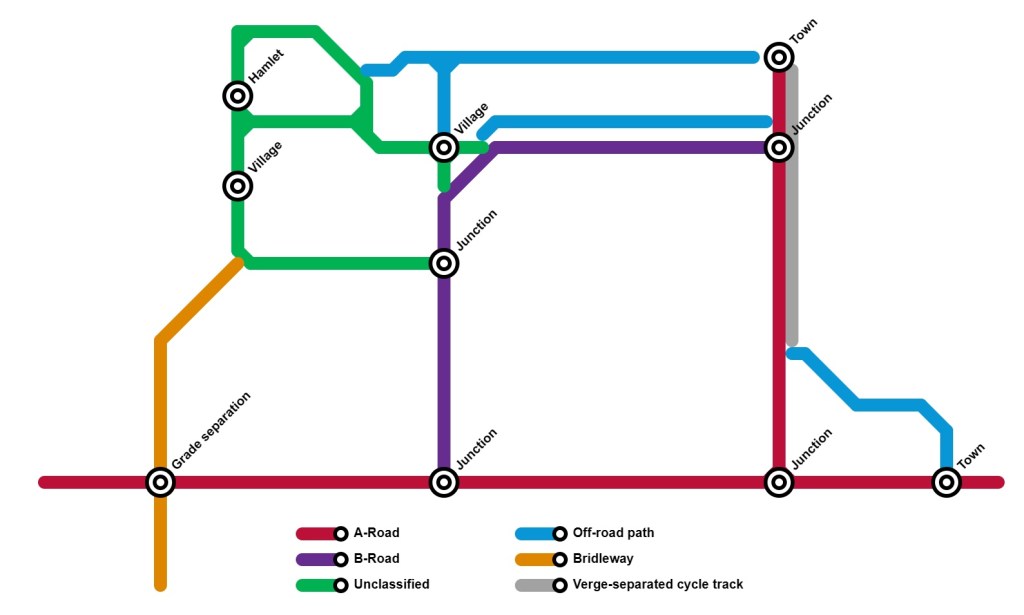

The image above considers some of those questions. We’ve decided the A-road is strategically important. We also think the B-road is needed for network resilience, but the longer term plan involves diverting it around the village so we can do something better with the unclassified network to the west. Getting people to the towns takes them east and so perhaps there is a northern off-road path to connect to the northern town and then a combination of a parallel off-road path north of the B-road which is also an agricultural access road, a verge-separated cycle track along the A-road within the highway footprint and then another off-road path which take people into town through quiet streets.

To the west, a section of unclassified road becomes a bridleway with a grade-separated crossing of the A-road network serving leisure cycling rather than daily transport functions because the next settlement is longer distance away, but it still connects with another area which has been planned in the same way. The unclassified roads connecting the villages and the hamlet are now only useful for those using cars for access and as such, the speed limits have been reduced, the roads traffic calmed and in some places, new footways have been added. The bus route using the B-road stops on the little by-pass, but there are now covered cycle racks there to help those from the western village and hamlet to access a service they now feel safe to reach by cycle. The village can now repurpose space in the centre for public space and a local market.

So what is to be learned from this? Put simply, we need a network plan and the good news is that it is all scalable so it doesn’t need tackling at once. In England, we have the Local Cycling & Walking Investment Plans approach to network planning which is underpinned by technical guidance. We think there are two significant problems with the guidance. First is that it can lead to an awful lot of data collection and route planning which doesn’t always help us think in terms of the basic idea of people needing and wanting to get to places and in the rural context, we are very interested in connecting places as the basic level of service needed. This is primarily a political discussion rather than a data discussion. In any case, the data will tell us is that nobody is cycling on busy rural roads, but people want and need to get somewhere.

The second problem is the guidance makes absolutely no reference to the motoring network. We simply cannot design a cycling network (and to some extent, but more locally, walking and wheeling networks) without thinking about the motoring network. In general, we are trying to unravel cycling from motoring in order to maximise comfort, attractiveness and safety. That doesn’t mean complete separation, it means we can integrate where is is safe to do so (or can be made safe to do so) and then invest where it’s not on separated provision.

Unless we consider and have a proper conversation around what is an appropriate motoring network, how can we design a cycling network? This is not about preventing motoring access. Our example above maintains motoring access, but it considers what is necessary from a strategic perspective and then works from there. This doesn’t just apply to rural places, but it can be more challenging than in urban areas where there might be more network planning flexibility.

Once we have a network plan, we think there are some important points to consider, especially as plans should be live, have political support and updated as conditions and contexts change:

- Adopt it in policy via an appropriate consultative and engagement process to give it weight.

- Get some early feasibility done and at the right scale.

- There will be obvious barriers – this is a long-term plan and we might need to do things in stages.

- Develop a delivery plan. This is absolutely key because without one, there is no focus on getting things changed on the ground.

- Early interventions can start to build momentum and support for delivery.

- Accept that this is about providing a basic level of connection and cannot ever compete with high benefit to cost ratios of urban schemes.

- Sometimes quick and dirty does the job. We can come back and adjust and adapt later.

- Don’t be afraid of getting things wrong and build in appropriate contingencies in cost and programme to delivery plans, and most importantly, be completely open about this from the start.

- Don’t give up in the villages and the town fringes because bad experiences mixing with fast and heavy traffic there will put people off next time.

Map data © Google 2025

Let’s look at three examples from South Zeeland in the Netherlands which is the least populated part of the country. The map above shows the villages of Terhole, Hengstdijk and Vogelwaard. At the regional level, they lie off the Dutch national road network.

The first example is the simplest. In order to stop drivers using Hengstdijk as an alternative to the main road (but not national road) which skirts the edge of the village. There is a handful of dwellings and field accesses along the road, and so local traffic is permitted access, but other than that, it is a local cycle route (above).

Above is the southern entrance to Tehole which is a great example of how driver behaviour is managed as well as how people cycling are protected. The village is bypassed by the national road network which has enabled the village street layout to be made more people-friendly. The island above is a feature on the village boundary which acts as a speed-reducing device for drivers and it’s where people cycling join and leave a cycle track which connects to the town of Hulst to the south. It is just possible to see that oncoming cyclists (over on the left) use the island to cross the road in two parts to access the two-way cycle track to the right which heads on to the market town of Hulst to the south.

In the village centre, people cycling are mixed with traffic on a very quiet street with a 20mph speed limit, while people walking and wheeling are provided with a footway. There are no road markings and every so often, there is horizontal deflection using the planting and the design of integrated on-street parking. It is a nice example of how a bypassed village can recapture some of its original peace and character. The national road is far easier to drive along that going through Terhole, but from a resilience perspective, it is still possible to divert traffic should there be a collision or because of works.

Our third example is Vogelwaard (above). Along with Hengstdijk and Kloosterzande to the north, Vogelwaard has a fairly important local road passing through it. While the three villages are bypassed by the national network over to the east, they carry a fair amount of locally generated traffic, including agricultural and industrial concerns which means some larger vehicles that are not really compatible with village streets.

Vogelwaard had been treated with a 20mph speed limit, traffic calming, village gateways transitioning cycling between two-way cycle tracks and mixing with traffic and in the village core and public realm works to provide a sense of place. However, traffic levels were still unacceptable and so a project was developed to bypass the village with a road that would also serve the Royal Kerckhaert Horseshoe Factory, an important local employer.

Map data © Google 2025

The image above shows the new road which bends to the right with the original alignment to the left. The new road is not wide and the speed limit is set at 40mph. This is no gold-plated, land acquiring, protest attracting bypass that we’d see in the UK.

Map data © Google 2025

Traffic lane widths are kept to a minimum, with overrun areas for larger agricultural vehicles and apart from the crossing refuge shown above, there no centre lines. This is all about managing driver speeds. In fact, the crossing refuge allows cycle traffic to cross the new road to access a quiet rural road beyond (to the right), and any motor traffic from there now has to use the little bypass. The project doesn’t stop there. Now the bypass is open, the municipality of Hulst has turned it’s attention back to making the village a better place and of course, being the Netherlands, this starts with an upgrade of local utilities and drainage.

Does our insight inspire you?

We’d love to have a chat about your project and so why not drop us a line at contact@cityinfinity.co.uk