The use of toucan crossings has been a standard feature in the provision of shared-use paths for many years in the UK. While shared-use layouts can be perfectly reasonable in the right context, the use of toucan crossings can be problematic to users of large, non-standard, and adapted cycles; and are especially problematic for those who are unable to dismount.

Because toucan crossings are primarily designed for pedestrians and are shared by people cycling, the position of the push-button unit is a key issue in terms of set-back from the kerb (depending on the arrangements of the overall signals assembly), offset from the crossing studs (generally 0.5m), and the orientation and the mounting height (1000mm to 1100mm).

Access to push-buttons may be less of an issue where cyclists have them to their left or right before crossing, and can stop next to them (assuming the crossing is wide enough to turn and cross), but where cyclists arrive perpendicularly to the road being crossed, push buttons are at their most problematic.

Figure 1 above is an illustration of the issue. The seating position on this example tricycle is 1.5m from the front and even with the front in line with the kerb line, the rider cannot reach the button without dismounting and having to stop the cycle rolling down the dropped kerb (most users will wish to be back from the edge of carriageway).

Current guidance has yet to deal with this problem explicitly, however, Local Transport Note 1/20 Cycle Infrastructure Design has paragraphs which have relevance as follows.

- Summary Principle 5 (page 10) states “cycle routes must be accessible to recumbents, trikes, handcycles, and other cycles used by disabled cyclists.”

- Paragraph 6.6.5 relates to registering cyclist demand at bus gate signals, but states “care should be taken to ensure push-buttons can be reached by cyclists who cannot dismount, including from a recumbent position.”

- Paragraph 8.3.2 relates to access controls, but states “access controls that require the cyclist to dismount or cannot accommodate the cycle design vehicle are not inclusive and should not be used.”

- Paragraph 10.6.17 relates to cycle-only phases, but states “care should be taken to ensure push-buttons can be reached by cyclists who cannot dismount, including from a recumbent position.”

The problem is also noted by Wheels for Wellbeing in “A Guide to Inclusive Cycling, 4th Edition 2020” where it states, “buttons at pedestrian crossings may be out of the reach of cyclists who are low to the ground (e.g. recumbent cyclists), or positioned so close to the road that a hand cyclist will have to put their front wheel into the road to reach the button.” (Page 48).

There are two solutions to the problem.

- Use of detection to register crossing demand. Where there are multiple crossings, they could be linked to call demand ahead of cyclists reach the next crossing, subject to wider signalling strategy considerations. However, detection may not be suitable in locations where pedestrian and cycle traffic closely passes the crossing and would trigger a false demand.

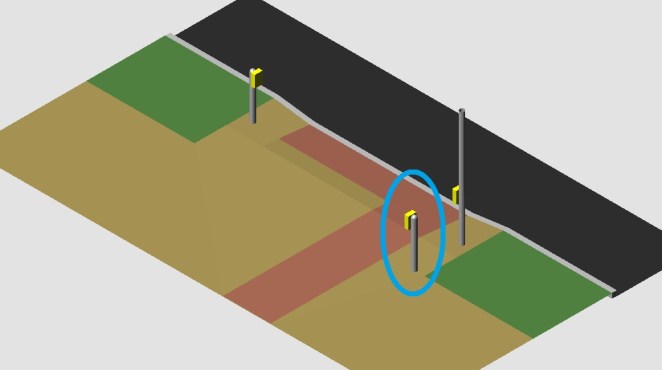

- Use of supplementary push buttons on short posts set back from the kerb so users of non-standards cycles aren’t at risk from entering the carriageway – where a crossing has ‘L’ shaped blister tactile paving, the supplementary push button poles should be on the opposite side of the crossing stem to avoid confusion by visually-impaired pedestrians who may inadvertently use the supplementary push button and must deal with a longer crossing distance (Figure 2 below). This option will be problematic on crossing islands with limited space and where providing supplementary push buttons would “overlap” between crossings.

If we are struggling to achieve either of these with our designs, then they need to be rethought because at the moment, toucan crossings simply don’t provide the level of accessibility we should be demanding.

We imagine streets, neighbourhoods, towns and cities where walking, wheeling and cycling are the safest, easiest and most natural choices for local trips. We design for sustainable mobility and can help you to create better places – take a look at our website for the services we offer.

One thought on “Better Toucan Crossings”